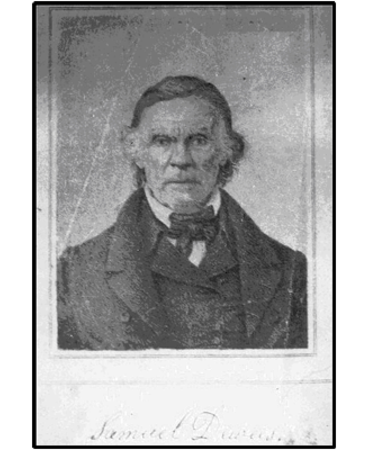

Samuuel DeWees – Fifer of the Revolution

Extracted and re-titled by Vee L. Housman from the book:

A HISTORY OF THE LIFE AND SERVICES OF CAPTAIN SAMUEL DEWEES,

A NATIVE OF PENNSYLVANIA, AND SOLDIER OF THE REVOLUTIONARY AND LAST WARS,

ALSO, REMINISCENCES OF THE REVOLUTIONARY STRUGGLE

(Indian War, Western Expedition, Liberty Insurrection in Northampton County, Pa.) and Late War with Great Britain.

IN ALL OF WHICH HE WAS PATRIOTICALLY ENGAGED.

The whole written (in part from manuscript in the hand writing of Captain Dewees,) and compiled

BY JOHN SMITH HANNA Embellished with a lithographic likeness of Captain Dewees, and with eight wood-cut engravings, illustrative of portions of the work.

Joy there is in contemplating noble worth,

Worth often neglected and despised,

Worth that oft in hours dark stood forth,

As thunderbolts of war—yea eagle eyed.

BALTIMORE: Printed by Robert Neilson, No. 6, South Charles Street

1844 Entered according to the Act of Congress in the Year 1843, by Captain Samuel Dewees, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court, Maryland

CAPT. SAML. DEWEES

Lith of Ed Weber & Co., Baltimore

(Copy of the photograph always kept in the family Bible of Thomas DeWees

Copy made June 1961. The same picture is on the Frontispiece of the book”)

SAMMY THE FIFER

Chapter 1

[Pg. 31] I was born in 1760 at Patton’s Furnace situated about ten miles from the town of Reading, in Berk’s County, Pennsylvania. My father’s name was Samuel Dewees, and was by trade a leather breeches maker. At the time of my birth however, my father was master collier at the above named furnace. I was the fourth child. John was the eldest, the rest with myself, were born in the order following: William, Elizabeth, Samuel, Powell, Thomas and David. All are dead, with the exception of myself and my brother Thomas, who now lives in Wayne County, Ohio.

Owing to difficulties always attendant upon poverty, my father sought places for all of his children; places where he had good reason to believe we would have been treated with kindness or else he would not have placed us there.

This seems to be a hard and sad alternative in any instance, but those having had the trials of poverty; who having had to contend with every species of poverty with which they have been rifely beset; who having had to struggle against the tides of ill fortune in a cold, oppressive and unfriendly world, when rearing a large family of small children, can best tell what a painful trial it is to break the family ties of kindred feeling and hourly intercourse by a separation thus, at a tender age.

I was nearly five years old when my father bound me to one Richard Lewis, a Tory Quaker who lived in what was then (and suppose is yet) called Poplar Neck in Berks County, Pa. He possessed (contrary to the nature in general of that virtuous people denominated Friends) but little of the milk of human kindness.

He treated me not only with harshness and rigid severity but with the most brutal and wanton cruelty. Cruelty which has stigmatized him and made him to appear to couple himself with my earliest associations of thoughts within my own mind in recollections as a demon, throughout a long life with which I have been blest by Almighty God.

I was undoubtedly, as most children are that are not blest with a proper culturing hand in youth, inclined to be mischievous—and Lewis was among the last of men (and his wife among the last of women) to make any allowance for the aberrations of juvenile nature. He kept a whip constantly laid up for me, and often, very often, used it, more to gratify a savage or fiendish and ferocious disposition of heart than to correct a fault, many of which were very trivial in themselves.

During the winter seasons whilst I was with him it was made my duty to tie up and fodder the cattle, to house the sheep, feed the hogs, cut fire wood, go to mill, etc. One winter night after having been in bed sometime, Lewis called out to me in a very surly tone, “Sammy!” I answered (as I was taught), “What?” He then said aloud, “Did thee put in all the sheep?” I replied that I did.

“Thee lies thee dog, come down here!” I jumped out of bed and put on my little sheepskin breeches and came downstairs. It was a bitter cold night, the snow was fully knee deep to a grown person and had a crust upon it. After I came downstairs I was in the act of putting on my stockings and shoes when he bawled out, “No thee dog, thee shall go without thy shoes and stockings.” And with a clout alongside of my head he drove me reeling out of the house into the snow barefooted.

I found some of the sheep out and after penning them up which was as quickly done as possible, I returned to the house almost frozen, my feet particularly, and with the blood trickling down my shins. Lewis, with a blow on my head, had sent me out of the house, but his work was not finished, until now. With another he sent me off crying to my bed, accompanying me on my passage thither with the epithets rascal, dog, etc.

At another time he called out at the top of his voice, “Sammy, Sammy!” I answered, “What?” and then neared him. “Go,” he said, “and draw a pitcher of cider.” I took the pitcher out of his hand and went down to the cellar and drew it full of cider, or rather more than full, for I could not shut the spigot. Knowing what I would get, I was very much scared and ran and left the cider running out of the barrel and pretty fast too. I was afraid to call or to run and tell him of the disaster, I ran up and left the pitcher in the room and took French leave for the moment.

Lewis hearing the cider running longer than necessary to fill the pitcher repaired to the cellar in double quick time and stopped it. He had no sooner ascended the cellar steps than he bawled out in an unusually angry tone, “Sammy, Sammy!” I then knew the time of day and having no protector to fly to I had to obey the citation of this monster of cruelty who took down his whip and set to work deliberately to plat a cracker and affix it to the lash. This cracker he tied full of knots ordering me at the same time to haul off my roundabout and jacket. This done, he set himself to work to beat me. He whipped me until he became tired. He then stopped a short while. After having rested himself he then examined my back when he stripped off my shirt. Seeing that it looked pretty well scarified already but yet not enough to glut his vengeance, he gave me a severe cut upon it when he had bared it and then bade me to be gone for a rascal and do my work.

At the time there was a shoemaker by the name of Gideon Vore, a Quaker who lived in Reading but who at this time was at work in the house of Lewis. He remonstrated sharply with Lewis against the cruel beating which he gave me. Lewis not taking it well, angry words ensued upon both sides. Vore being a pretty resolute fellow backed his just spirit and told Lewis plainly that he would soon see whether there was not a law to be had to protect me against such savage usage. He put on his coat immediately and started for Reading. Lewis, seeing he was determined, followed him out of the house and prevailed upon him to come back. I did not know upon what ground he succeeded in diverting him from his purpose, but suppose that he promised to Vore that he would not flog me so severely again.

Among the cattle of Lewis there was one, a steer which had a white spot on his forehead, and I having found a nest full of rotten eggs in the stable conceived the idea (as I was letting the cattle out one morning) of target firing. So setting to work, I blazed away at the white spot on the steer’s forehead. I stood at some distance from him and was amusing myself very much and proud too, that I could hit so near to the white spot as I did.

Lewis beheld the sport, innocent and harmless as it was, but he did not relish it very well. Not having a hand in that frolic he thought it was best for him to have one in which he could and where he could show himself off as principal actor and master of ceremonies too.

After beholding my sport of egg-shooting, he provided himself with a hickory weith and bawled out, “Sammy!” in a lusty manner. I answered, “What?” He cried out, “Come here!” I went to him. He then said, “Sammy, thee has had fine sport this morning and I want a little too.” He then ordered me to strip off my jacket. I did so, or rather he took it from off me. He then began to play away upon me with the hickory weith and I began to dance to its all inspiring music of unmerciful harshness and so we had it until both became tired.

If he had promised to Vore that he would not again flog me so severely, he broke his promise now, for in consequence of my having to endure such an unmerciful flogging at his hands, my back was well striped and exceedingly sore indeed.

There was a corn-husking one night at my master’s brothers. All in the family were invited and went but myself. I wished to go but the old man ordered me off to bed. The thing troubled me so much that it appeared it was the whole engrossing subject within my mind when asleep.

I at length arose out of my bed and started off undressed to go to the husking and fortunately was met more than half way, as they were returning home again, which must have been well on towards daylight. They took hold of me and found I was asleep. This was the first knowledge I had of my having been asleep, after which I was very cold.

At another time when I was engaged in driving the cattle out of the stable, there was one that I was much plagued with for I could not get it from the stable door. I picked up a piece of a knot of wood and let slip at it and knocked it down. My mistress seeing this took after me cudgel in hand and yelling like a savage. I ran off without the word “go” and streaked it into a rye field for shelter.

I heeled it through the rye which was then in blossom. She tried to heel it too but “couldn’t come it.” Once and a while I would pop my head above the rye in order to see where the old vixen was. When I perceived that she in her course or tacking was likely to overhaul me, I would slide into another point of the compass and ensure the safety of my person thereby. I had my sport in fooling her until almost night for I was determined not to surrender to petticoat government or authority in that instance.

Not being willing to return to the house that night, I pushed off in search of quarters which I obtained, for I billeted that night in a neighbor’s barn and was without a supper. Next morning my master’s son came after me. The owner of the barn understanding that I was there, talked with Lewis’ son about me and made him promise that I should not be whipped. Upon this condition I capitulated and went home with him, but if I did, I went trembling every step of the road; this because I knew something of the characters I had to meet.

When we arrived I was about to “catch it,” but young Lewis plead with his mother for nearly an hour ere she waived her intention. She very reluctantly agreed to bury the hatchet for a time and so I escaped punishment at that time. She might have agreed sooner to have let me slip, for nothing was more easy than to have given me two whippings at one and the same time thereafter, a game which she could play and which I understood very well. But she was satisfied with the armistice established on that occasion. This will not be wondered at, as it is natural for persons, particularly youths to put off the evil day as far as possible in the future.

I was sent one day to carry dinner to my master’s son where he was ploughing in one of the fields of the farm. When I had gone to the distance of two or three hundred yards from the house, I was met by a large boar belonging to Boston Murrier, who was one of our neighbors.

The boar advanced towards me with bristles erect and running sideways as is the attitude of battle among hogs. When I would stop, he would stop and champ and froth like a prancing charger would his bridle bit. When I would endeavor to go on (for I had a hope that I could have reached a fence not very far off, he would run sideways after me. I contended with him in this way for some time, but found it impossible to reach the fence. I then dropped my basket containing the dinner and had the hope that as I could run towards the house, he would have stopped to devour the contents thereof and let me go.

I started at full speed for the house and seeing my master’s daughter at the woodpile, I called aloud to her. The boar however did not stop to taste its contents but ran after me, overtook me and threw me down. The daughter called my master who was then in the house. They both ran accompanied by a large dog and succeeded in taking him off me, but not until he had sunk his tusks into my back so that a finger might have been thrust through into my inside. They succeeded with the help of the dog in catching him which when they did my master with a large stone broke off his tusks and some of his teeth and then let him run.

The belief was that had not help been thus afforded me, he would have torn me to pieces, and had it not been that my master’s daughter was at the time at the woodpile, I might have cried in vain, ere help would have been extended to me. This woman was married and lived in Reading, but was on a visit to her father’s at the time. She was quite another kind of woman when compared with her mother. She was always very kind to me when on visits to her father’s and upon this occasion manifested her joy in my rescue and was very tender to me in my then injured and helpless state.

Lewis sent Murrier word that if he still would permit the boar to run at large, he would shoot him wherever found. Murrier put him up to fatten, which no doubt secured the person of others from his fierce attacks thereafter.

Whilst I remained in the family of Lewis another accident befell me which came near ending my life. It happened in hay harvest. We were engaged in hauling hay and whilst taking in the last load into the barn, a son-in-law of Lewis’ drove the wagon wheels over a stump which pitched me off head-foremost against a rock and with such violence as to crack my skull. I was much injured by this accident for a time and must attribute it in a great measure to my own carelessness and contempt of danger. For after I had finished building the hay upon the wagon, I laid me down upon my back on the top of the load, an act that no person in his senses should at any time be guilty of. It was foolish in the extreme.

Servitude with these cruel-hearted people was very irksome to me. When I look back upon the scenes of hardships that I was made to endure, the continual scoldings meted out to me and the unmerciful corrections I received at their hands, I can but liken myself to a person in the midst of a den of rattlesnakes, afraid to move in any one direction for fear of encountering the venomous fangs or bite of those having the power over me.

My clothing was of the coarsest cast. I recollect that when linen collars and wristbands were put upon my coarse tow-linen shirts, I was very proud indeed. In eating I was often the subject of pot luck. Lewis had a nephew that lived with him some time and his victuals like mine were often begrudged, as the saying is. This lad was perhaps eighteen years old and I remember that the old man lectured him occasionally upon the art of eating. One day the old man was lecturing his nephew upon eating, trying perhaps to break my back over the shoulders of the nephew. Said he to his nephew, “Thee should always quit eating and rise from the table hungry.” “Indeed Uncle,” said the nephew. “I always eat until I am full and then I like to take a good chunk of pie with me in the fist to eat after that again, by way of a finish to my meal as a topper out.”

Chapter 4 [IV sic]

[Pg. 77] Upon the breaking out of the Revolutionary War my father enlisted as a recruiting sergeant in the Continental Army. At the time of my father’s enlistment he lived in Reading, Pa. Sometime after his enlistment, he enlisted my two oldest brothers John and William and when he had enlisted a pretty good company of soldiers, he moved on and joined his regiment.

Shortly afterwards he fought at the Battle of Long Island. My mother and my two brothers accompanied him in this expedition to the north. In this battle the American loss was very great. The American troops however fought as bravely as at any battle during the war of the Revolution.

Shortly after the Battle of Long Island, the regiment to which my father and brothers were attached, laid with Washington at White Plains, and after his retreat from there, it was ordered on to Fort Washington. This fortress was attacked on the 16th of November, 1776, by four divisions of the enemy and at four different points. The garrison fought bravely whilst it had ammunition. When this became exhausted it capitulated. My father was wounded and by capitulation became a prisoner of war and was thrown into a prison ship where he endured great privations and sufferings.

When my brothers informed my mother of the situation of my father, she followed his destiny and threw herself into the British camp. She begged permission of the officers to go on board the prison ship and minister to his wants, relieve him in his sufferings and soothe him as far as practicable in his suffering conditions.

She begged this privilege of the British commander and officers for God’s sake, but for a long time they were deaf to her entreaties. After repeated importunities her request was at length granted. She was not very long on board the prison ship until she fell sick with disease contracted in her constant attendance upon my father amidst the sickening staunch arising within the ship. This sickness was owing to that great pestilential stench created by so many sick and wounded soldiers being huddled together in so confined a place as a prison ship.

My mother begged so hard of the officers in the midst of her sickness for the release of my father that they were induced at length to let him off upon parole of honor, as it was called, the purport of which was that he was not to be found bearing arms thereafter against Great Britain.

My father and mother in part recovered, set out in a weak state of health for home but upon reaching Philadelphia my mother was taken ill again and shortly afterwards died in that city.

Not long after the event of my mother’s death, my father reported himself at camp and joined the army again. But as he durst not fight against Britain with any degree of safety, it was thought most advisable to send him again to Reading in the capacity of a recruiting sergeant.

Whilst my father was at Reading obtaining recruits, he was informed of the cruel treatment I received from Lewis and family. He visited me and told me to come to town in the course of a few days thereafter. I did so. He then enlisted me as a fifer. At this time I suppose I was about or turned of 15 but quite small of my age. Soon after my enlistment, my father who had enlisted a good company of men marched them off to join his regiment which was stationed somewhere in Bucks County, Pa.

At this time the regiment being again full as to numbers was ordered on to West Point where there were a great many soldiers. Whilst we laid at West Point in the latter part of the summer of 1777 the American soldiers were busily engaged in building a great number of huts for winter quarters. They erected two rows which extended more than a mile in length. The parade ground which extended the whole length in front, was from 250 to 300 yards broad and was as level as the floor of a house. There were two or three brigades of soldiers there at that time, to the first of which our regiment was attached.

My father was ordered back from West Point to Reading again and from Reading he was appointed and ordered on to take charge of the sick and wounded soldiers on the Brandywine Creek in Chester County. Pa. Brandywine meeting house was at this time used as a hospital. My father marched thither and took charge of it as superintendent and I accompanied him.

We had not been very long at Brandywine meeting house before the Battle of Brandywine took place. This event occurred on the 11th of September 1777. Although General Washington and the Marquis (then General) de la Fayette and their brave troops were forced to retreat, yet Washington struck the iron whilst it was hot and did his part faithfully. He attacked the British infantry whilst in the act of fording the Brandywine creek at Chadd’s Ford, and had it not been for the great superiority of numbers upon the side of the British, advantages would have been great and decided. This Washington was well aware of, as the British soldiers when emptying their pieces could not load whilst they were in the stream for they could not procure a resting place for the butts of their muskets. Had they attempted to have done so their muskets would have been rendered useless by the water.

It was said after the battle that the waters of Brandywine were reddened with the blood of the slain soldiers of the British army. The battle was fought so near to the meeting house that the firing of cannon shattered the glass in the windows.

I remember well that the glass came rattling down constantly whilst any remained in the building. The wounded soldiers were brought in great numbers to the hospital. Those engaged in bringing them drove as fast as they could possibly drive under existing circumstances. Upon their arrival they would hastily lift the wounded out of the wagons, place them on the ground in front of the hospital and return as soon as possible to the field of carnage for another load.

To hear the wild and frantic shrieks of the wounded, the groans of the dying, and to see the mangled and bloody state of the soldiers upon the arrival of the wagons; to see the ground all covered over with the blood and blood running in numbers of places from the wagon-bodies, was enough to chill the blood in the warmest heart. To see the distorted features of those brave men, writhing in the most keen and inexpressible anguish, when harshness of handling or removing in haste became not only necessary but was tenderness in itself in efforts to save them from a lawless, inhuman and insulting cruel foe.

These were the hours of darkness and of sore trial. Those of us at the hospital carried the wounded soldiers into the meeting house as fast as we could and laid them to the hands of the surgeons who dressed their wounds as fast as possible and sent them off in wagons immediately afterwards towards Philadelphia. Oh, what a scene!

The skirmishing engagements and regular battle lasted from daylight until almost sunset. This battle was a hard one. The heat of the day was very oppressive, the men suffered severely and no doubt many soldiers died from exhaustion alone. The cry for water was the most distressing. Soldiers would come to soldiers and beg for God’s sake that they might receive but a little water to quench their burning thirst. Wherever canteens were beheld by these famishing soldiers slung upon others, a descent would be made upon them. In many instances when assurances were given that their canteens were empty, no credit would be given to the assertions, but the famishing soldiers would tear the canteens from off the shoulders of their possessors and examine them themselves ere they would be satisfied that they were empty.

Many of those unsatisfied and perishing heroes returned again to the battle and many no doubt died from exhaustion. Others fell dead on the battle field from the deadly arms of their enemies. Others fell covered with wounds and with glory contending with odds against them in defense of [their country].

My father and his soldiers were now under the command of Colonel George Ross of the 11th Regiment and remained at Brandywine meeting house for the purpose of burying the dead. This they continued to do until a body of British light horse were beheld coming up at full gallop. My father ordered his men to fly instantly to the woods, telling them at the same time to halt there until he should join them. He then bade me to run fast for the woods and take care of myself, whilst he was the last to leave.

I being pretty fleet of foot, I halted within sight until the light-horsemen rode up in front of the meeting house. I felt anxious to see what they would do. Upon halting they all dismounted. There was a dead soldier lying on a bench in front of the church, covered with a blanket. I saw a British horseman draw his sword as soon as he dismounted and advance to the bench and run it through the body of the dead soldier. The beholding of this spiritless action satisfied my curiosity and I “heeled it like a major” and was not the last of the party in gaining the wood.

Upon the horsemen taking the route we had taken we were again induced to take to our “scrapers.” I ran into a house where our Colonel had boarded and picked up a pair of boots that belong to him and carried them with me. The retreat was ordered to Philadelphia whither we were now bound. We all became scattered in the woods after dark and my father and myself took our course across Delaware County in the direction of Philadelphia.

We traveled some considerable distance that night and at last arrived at the house of a good American friend, a true friend to the weary and despised soldier. This man gave us a hearty welcome to his house, took us in and gave us to eat and drink. He then conducted us up to his garret and made us a bed upon the floor so that as he said, if any of the British scouters should come they might not be able to find us. Here we rested our weary limbs till almost daylight and then pushed on for Philadelphia barracks. We played rather hide-and-go-seek upon the road, keeping a constant look out for the British or British scouters, but we were not surprised by any of them on our route thither.

When we arrived at Philadelphia barracks, we found but a few soldiers there. I do not recollect whether General Washington arrived before or after us at Philadelphia but think that he did not arrive there before us as his march could not have been as rapid a one as ours.

He had halted at Chester for the night, only eight miles from the scene of action and had his artillery and baggage to retard his progress. It is therefore, questionable in my own mind whether he arrived at Philadelphia on the same day that we did.

Shortly after our arrival at Philadelphia, I carried the boots (I had brought with me) to Col. ______ who came to his door and received them from me. He said, “You are a fine little boy,” but never said as much as thank you, or offered me anything to eat or to drink as a remuneration for my trouble of carrying them so great a distance to him. After delivering his boots to him, I returned to the barracks scratching my head, wishing at the same time that I had given them to the old farmer that kept us in our flight to Philadelphia.

Chapter 5

[Pg. 124] One day prior to our leaving Philadelphia, I was out taking a walk around the city. On my return to the barracks I espied some fine looking cabbage in a back lot. I mentioned this to my comrades and two of them and I agreed to go that night and procure a head apiece. Accordingly, after dark we sallied forth and entered the lot. I pulled up a head and was leaning upon the fence waiting for my companions. Whilst in this position I was surprised and taken prisoner by a strapping big Negro who clasped my body fast in his arms. At this moment my comrades ran away and left me in the lurch.

The Negro took me into the house, crying out at the same time, “I have got a thief! I have got a thief!” I had not only to beat this mortification, but another for he made me carry the head of cabbage into the house in my hand.

There happened to be some company with the man of the house that night and I was plagued a good deal by some of the gentlemen that composed the company. Some was for having “this” punishment inflicted upon me, and some was for inflicting “that.” The circumstance of the Negro having been bailiff and catching me as he did, created some fine sport for them.

The gentlemen of the house at length asked me my name. I told him it was Samuel Dewees. “Samuel Dewees?” said he. “Yes Sir,” was my reply. He then whispered to one of the persons present and then asked me where my father lived. I told him that he had lived in Reading. He then asked me what my father’s name was. I told him his name was Samuel Dewees. He next asked me what business my father followed. I answered that he was by trade a Leather Breeches Maker.

By these my answers to his interrogatories, he found that he and I were second cousins and he and my father were first cousins, his father’s father and my father’s father having been brothers. This man’s name was William Dewees who was then the High Sheriff of Philadelphia.

He, upon finding out the family connexion, did not strive as many do to deny the claim of kindredship, but told me to take my cabbage with me and to come back the next day and bring my knapsack with me. He said he would give me some bread, meat, potatoes, etc. I was very glad, however, to get off as I did and the least of my thoughts then were about returning. Still, I would have gone back again in a few days, but the British taking possession of Philadelphia in a few days thereafter, Sept. 26th, 1777, we were forced to fly from the barracks (situated in what is now the Northern Liberties and laid towards Kensington) and from Philadelphia. We were ordered on board of the shipping which contained the sick, as also the soldiers which had been wounded at the Battle of Brandywine. We immediately set sail up the Delaware river and landed at Princeton, Jersey. General Washington moved on with the main army to Lancaster.

The British after they took possession of Philadelphia and whilst they held it, committed great depredations upon the friends of liberty residing in the city and for some distance around it, farmers particularly, upon whose substance they were continually foraging.

I recollect of hearing of one farmer who lived in the Neck and who was continually harassed by marauding parties. He had made a kind of closet or safe under the first and second steps of the stairs leading to the loft, and was able to displace and place the front of the step in such a manner as to defy detection. In this his wife kept bread, meat, butter, etc., etc.

One day he was engaged in digging his potatoes which were of the finest kind. Having taken his cart out to the field, his wife and children had gathered of the potatoes which he had dug up and filled the cart body. In the after part of the day a party of British came and began to fill their knapsacks with the potatoes which the cart contained. At this time there were the potatoes of a number of rows dug and lying in little piles from one end of the field to the other. He told them if they were minded to take his potatoes he thought that they might content themselves and be very well satisfied to get them for the picking up from off the ground without taking those that his family had already gathered into the cart. They laughed at him for his presumption to talk to them in that style and showered upon him a deal of opprobrious [disgraceful] language as his remuneration for his counsel and potatoes.

After taking as many of his potatoes as they chose, they directed their steps towards his dwelling. He followed them thither. Their first demand was bread, meat, etc., and commenced ransacking in search thereof. He told them there was not any bread about the house. This would have stood good for aught they could have done in their search had not one among the youngest of his children, a child just able cleverly to talk, betrayed the place of its concealment. When he told them in the child’s presence and hearing that there was no bread about the house, the child cried out, “Yes, Father, there is bread in there,” pointing at the same time to the first step of the stairs.

This afforded the British soldiers a clue and they were not long in making themselves the masters of the secret deposits. With the bread, meat, etc., hid in this secret cupboard there was a large crock of very fine candied honey, all of which became their booty. It was all borne off by them to camp, leaving not as much in his house as a morsel of eatable kind to supply his children with a supper.

Chapter 6

[Pg. 133] After retreating to Princeton from Philadelphia we did not lie long at that place. From Princeton we went to Bethlehem, Northampton County, Pa. [Pg. 134] Whilst we laid at Bethlehem I went frequently to the Nunnery which was used as a hospital to see the surgeons dressing the wounds of the wounded soldiers. Among the number I remember seeing two soldiers, one of the name of Samuel Smith, whose whole leg and thigh was dreadfully mangled by a cannon ball. The doctors amputated it close up to the body. Smith recovered and learned to be a tinker. I often seen him after the Revolution.

The other soldier was shot through the neck, the ball had passed in at one side and out at the other. He recovered, but his neck was always so stiff afterwards that when he wanted to turn his head to look in any direction, he had to turn his body therewith to enable him to do so. I often seen him also after the Revolution.

About this time, October or November 1777, the small pox broke out in portions of the army and my father was sent to take charge of the sick to a place where a considerable number of soldiers were encamped not far from Allentown, Bucks County, Pa. Upon my father’s reaching there, a large house that had belonged to a Tory was converted into a hospital. All the soldiers that had not been taken with the small pox were immediately inoculated. My father had a room in this building exclusively to himself and had the care of all upon him. He drew the rations for the soldiers and dealt out the same to them. He had to superintend the preparation of victuals, drinks, etc., for the sick and assisted in nursing them in their sufferings.

My father caused myself to be inoculated with the real small pox and I became very sick. The cause of this, however, was with myself. I did not restrain myself as I should have done, I did not keep from eating salt and strong victuals, I would sometimes partake heartily of my father’s cooked meals, etc. My appetite was keen and I left nothing undone in my endeavors to satisfy it. I even resorting to novel methods to obtain what was satisfying to it. One was to sharpen the end of a stick to a point and after fixing a piece of bread upon it, I would hide it behind my back and slip up to where some of the soldiers were engaged in cooking salt and fat meat. Watching an opportunity, I would dip my bread into their pans or kettles and then run away and feast myself upon it at my leisure.

I recollect that once my father had some excellent gammon cooked and had placed it for safekeeping in a cupboard which he had forgotten to lock. This I got at and ate it all, a mess sufficient for two hearty men. After this indulgence I fell very sick and remained so for some time or at least it was a good while before I recovered my health properly.

My sister Elizabeth was bound out about 10 miles off and my father having heard that she had had the small pox went for her and brought her to see me as also to attend me in my sickness. She remained here until I recovered, and I may state until we both left after the decease of my father which took place not long after he brought her to camp.

A word or two more relative to my sickness. I was very sick indeed and suffered much although there were in all but thirteen pocks [pox] upon me, the rest having struck in (or had not come out at all) in consequence of my own imprudence.

I had but got about again out of a sick bed when my father who was so constantly among the sick, fell sick himself and died in the course of three or four days after he was first attacked. I cannot recollect what the disease was, whether pleurisy or fever. I believe, however, that it was the latter. I remember that the disease was not small pox.

I have here a very singular circumstance to relate relative to my father. In the room occupied by my father there was a fireplace in which there was a fire, the weather being then rather cold. From that room we had to pass through another before we could gain the entrance that lead into the house. My father was very much deranged on the morning of the last day of his illness, so much so that it required two or three soldiers to keep him in his bed. Towards noon he had become somewhat easy and had fallen into a gentle sleep. During this interval of quiet, my sister and myself were sitting at the fire. When he awoke from sleep, he sprang suddenly from the bed upon which he lay and dashed out of the room, passed through the entry and out of the house.

All within ran after him in order to secure him and bring him back to his bed. The yard was a very large one and in it stood a very large barn. We hunted about in the yard and searched the barn over and over again but could not find him. There were a number of fields upon the place but there was one in front of the house, a very large one that extended from the house to the woods, and we searched for him in every direction but without success.

My sister and myself were sitting at the fire mourning about him and wondering as to what could have become of him. In the evening he was seen in the large field and near to the woods, distant from the house about half a mile. Whilst we were fretting about him within doors, all at once a soldier cried out, “Yonder is something white,” (he being without any article of clothing except his shirt) “near to the woods,” and said that it must be Dewees. He with the other soldiers ran and found that it was my father. They brought him back to the house immediately. Where he had been wandering none knew nor could any conjecture, but he must have been running about all the time for his skin was very much torn by briars and thorns. When he was brought back he was quite sensible.

It being late in the fall and weather quite cool, he was very cold when he returned. Those that brought him back made him sit down at the fire in order that he might become warmed. Whilst he sat down with us at the fire he perceived us crying and he told us that he was not long for this world and bade us not to mourn for him. He then tendered good counsel to us and commended us to the keeping of the God of Battles whom he said was the orphan’s God and would protect us and take better care of us than he could were he to remain with us.

Some of the soldiers then helped him to get into his bed again. His words were true, for he died that night. The soldiers upon the next day made a box (for coffins were things almost unknown among us), and placed him in it and buried him with the honors of war near to some bushes which grew a short distance from the house. Other soldiers lie buried near that spot also.

Whilst we were paying the last respect and duty to his remains, some unprincipled soldiers had entered the room we occupied and taken a number of articles from his knapsack. The razors, box, brush, etc., which had belonged to my father were among the missing. This we discovered when my sister and I were gathering up his little effects after we returned to the house preparatory to our setting out for the place where my sister lived.

We were now left orphans truly, in the camp of our country, and I may state without friends. To whom then could we look for proper protection? Upon the part of my father’s comrades there was manifested every disposition of kindness, but what could their united friendship accomplish for us? They were without money, the government had not the power to supply them therewith, and General Washington’s every mental strength was aroused in action to keep a naked and starving soldiery together.

My sister and my brother Thomas were both bound out in the same family. I do not recollect that it was a Quaker family in which they lived but believe that it was, as the inmates thereof had many of the habits of that people, this excepted; humane conduct, the offspring of an enlarged possession of the milk of human kindness. For the residence of this family, my sister and myself at length started, and where we arrived on the same day. In this family there was another bound boy beside my brother, and of about the same age of my sister. This boy and my sister were taken sick and about the same time. The sickness I do not know whether I ever understood properly what it was but I remember it was some kind of a fever. Their sick beds were in a room up stairs and my brother and myself made a fire in the room and attended them.

We didn’t realize that their sickness was of so dangerous a nature as to produce death. Not seeing any degree of fear or anxiety manifested upon the part of the family in their case, for the old people seldom visited them, my brother and self being young, wild and inexperienced were more ready to sally forth in mischievous style. No doubt this caused serious reflections and regrets to both of us afterwards. The two of them were flighty or delirious often, and it was fine sport to us to see them (after we would throw powder into the fire to scare them) jump and clamber against the wall of the room. When they would rise thus, we had to put them to bed by the dint of our strength. This conduct was highly imprudent and as injurious as it was imprudent. I don’t wish to be thought attempting to excuse or justify it, for I could not if I desired to do so. But it was by far more the effect of thoughtlessness and an unchecked spirit of good humored levity, than it was that of a wicked or wantonly cruel spirit.

My sister grew worse and on an evening not long after, she died. We had told the old people of her situation but they manifested no great concern. When she was dying we called them and they came up, but the vital spark was fast quitting its abode of clay. It sped its way to Him who is a Father to the fatherless, the orphan’s stay and the widow’s hope. The old people laid her out and had grave clothes and a coffin prepared, and on the next day they took her in a light wagon to the Meeting House about a mile off and they buried her in a grave yard attached thereto. My brother and myself accompanied them. This must have been late in the month of December, 1777, or January ’78. I remember that the weather was quite cold.

The boy, although he lay very low, recovered his health again. The old people, I recollect, bestowed a good deal more attention towards him after my sister’s death than they had previous. When I reflect now upon the little kindness manifested upon their part towards these two sufferers, I am ready to ask how can any persons in life that have come to the years of maturity, act so undutiful a part to those that lie upon a bed of languishment and death? But are there not those to be found still, wherever we go, that have by their own unfeeling conduct in this sad extremity—this trying and dark hour, the hour of sickness and death—stigmatized themselves as cruel in the eyes of the humane, generous and just?

Affection possessed by brothers towards sister, and by sisters toward brothers, how pretty, how manly, how womanly, how virtuous, how just, how all-pleasing in the sight of the Almighty Being. Let me exhort brothers, to watch faithfully over the sick beds of sisters and never for a moment to so far forget the duties you owe them as to treat them with indifference or cruel neglect, but to let a tender hand and tender speech be ever extended to them.

I don’t recollect whether there were sons and daughters belonging to the family or not, if there were I never saw any whilst I remained in it. I stayed there until towards spring. During my stay I helped to chop wood, feed and take care of the cattle, etc. I recollect one job which was mine twice each day, that of rubbing the legs of a mare with a rye-band that had the scratches.

Sometime about the first of March I enquired diligently for, and found that the army laid at Valley Forge. I told the man I homed with that I was going on to camp. He tried to dissuade me from my purpose. He said everything to me that it was possible for him to say in order to scare me or fill my mind with fear. I told him that I would go and that nothing upon earth should be able to keep me from joining my own regiment or some other one if I could but reach the army. When he found that I was determined to go, he gave me an eighteen-penny piece for all the labor I had performed for him during the winter.

I bundled up my little all and started early in the morning, bending my steps towards Valley Forge.

I cannot remember the state of the roads at this time but remember well, however, that my shoes were very bad. When I travelled more than half way to camp, I became quite weary and hungry and had resolved in my own mind that I would stop at the first house at which I should think likely to offer me something to eat.

I had not travelled far after I resolved thus until I met a soldier. I enquired of him the way and distance to Valley Forge encampment and asked him also relative to a house ahead at which I might be likely to obtain something to eat. He then asked me if I had any money. I told him I had none. He said he knew better and with that he caught hold of me and took my eighteen-penny piece out of my packet. I than started off from him and ran as hard as I could, being in a fretting humor at my loss as well as in consequence of being very hungry and nothing in my pocket to supply me with food.

Whilst running in this fretting mood, I met an officer who asked me what was the matter. I told him I was going on to join the army at Valley Forge and that I had been robbed by a soldier of an eighteen-penny piece which was all the money I had possessed, and that I was then very hungry and knew not what to do. He thrust his hand into his pocket and pulled out a five dollar note (I do not recollect whether it was Continental or States money) and handed it to me. He then bade me to hurry on beyond the first woods and that when I should get down to a bottom I would come to a tavern and bade me to call there and get something to eat and to drink. His kindness made a deep impression upon me, so much so that even now at this late day after a lapse of nearly 67 years, he sits on horseback before me as plainly as he did then—the generous hearted soldier on whose face the lofty frown of indignancy is strongly depicted.

After this officer gave me the money for which I thanked him, he put spurs to his horse and rode on in pursuit of the soldier. I then went on my way rejoicing in a heart overflowing with gratitude to so kind a friend as he was to me in the dark hour of my extremity. I soon arrived at the tavern and done as the officer had directed me, and soon had victuals served up before me. I told the landlord and his wife how badly the soldier had treated me. After I had made a hearty meal, I offered to pay them for it and some drink, but they would not take any money from me. Perhaps my having told them of the affair or that of my seeking the camp in my boyhood, or both induced them to refuse any remuneration.

I had not been a great while there and as I was about to start, I espied the same soldier that robbed me advancing towards the house and was all covered over in front with blood. Being no little afraid at seeing him in this plight, thinking at the same time that he might fall upon me by the way and kill me for having informed the officer of his conduct. I ran back through the house and went out a back door. I think that I did not stop running until I arrived at the encampment at Valley Forge. I never knew how it was that he became so bloody, but had good cause to believe that the officer who was so kind to me had overtaken him and struck and cut him with his sword, for when he left me he was very much exasperated at his dastardly conduct in robbing me (then a boy) of my money.

Chapter 7

[Pg. 146] Upon my arrival at Valley Forge encampment I immediately enquired for the 11th regiment, it being (as I have before stated) the regiment to which my father and myself were attached. Having found where it laid, I went in search of a Sergeant Major Lawson, an old comrade of my father whom I soon found. He was very glad to see me but very sorry to hear of my father’s death.

I told Sergeant Lawson how ill I had fared through the past winter, how little compensation I had received, and of that little having been taken away from me. I next told him how generously I had been befriended by the officer that I met afterwards.

In the course of a day or two Sergeant Lawson made known my case to Colonel Richard Humpton who took me to be his waiter. With Colonel Humpton I fared very well. The Colonel was an Englishman and had held a Captain’s commission in the old British service in America, but upon the breaking out of the Revolution, he took his stand upon the side of the colonies and joined the patriotic army in defense of the rights and liberation of the colonies.

Colonel Humpton had a young lady with him whom he called his niece, but who became his wife in marriage shortly after the Revolutionary War was ended. This young lady he was in the habit of placing to home at some distance from the camp and from danger, and with her he placed me to wait somewhat upon her and to take care of her. Miss Elizabeth, although of high extraction, was quite unassuming and of industrious habits. She differed from the ladies generally of the present day. She did not think it unbecoming or degrading to understand and do the duties of housewifery. She did her own sewing and washed and done up her own, the Colonel’s and my linen, etc.

Relative to her acting the part of a washerwoman, I can speak confidently, for upon her wash days I always bore a part in her labors and washed for her (as the saying goes) like a major!

At one time he homed her in the family of a Dutchman not far from the Lehigh River. The Colonel sometimes joined us. The Dutchman was fond of fowling and often used an English gun belonging to the Colonel, the touch-hole of which was bushed with gold. There was a large pond (or mill dam) on or near to his farm and it was much visited by wild ducks. The Dutchman often rose before day and went out and laid in ambuscade and waited their approach. He being a good shot would often kill numbers of them and generally divided the spoils with the Colonel.

The next place where he placed her to home was near to Somerset Court House in Jersey. The Colonel had a wagon, four horses and a driver allowed him, and in this he sent his niece, myself and all his baggage to the above named place. The team was again driven to camp.

Whilst we homed at Somerset Court House a British officer had been captured and placed in the Court House which was guarded by American soldiers. One morning after getting out of bed about sun up, I noticed some men coming at a distance and thought that they were American light horse. I immediately ran down towards a large gate at the road side in order to see them, supposing at the same time that I might know some of them.

I had gotten within a rod or two of the road as the front passed me. They were moving very slowly and some of them looked at me. Casting my eyes towards the rear, I discovered by their regimental coats that they were British dragoons. I at this moment bethought me that I was dressed in a Fifer’s regiment coat and cap with horse or cow tail hanging thereon, and instantly dashed away at an angling direction across the field as swiftly as I could, not daring to look at or to stop at the house to awake Lady Elizabeth, but ran until I gained the elevation in the fields, towards the wood.

Quickly after I had commenced to take French Leave of them I looked around and discovered that they were moving very fast. Whether it was seeing me running at such a speed that caused them to gallop off so furiously as they did, I know not. They might have thought that I ran to give intelligence to some detachment of soldiers not far off and that they knew not was stationed in the neighborhood. But if they had thought that I was making an instrument of myself for this purpose, they might have hindered me by shooting me and there was the gate, at it they might have entered the field and captured or killed me.

When I arrived near to the woods I looked around me and discovered Somerset Court House all in a blaze. I feel confident that not more than 15 minutes had elapsed from the time they passed me until the Court House was thus enveloped in flames. Before they fired the building, they released the British officer and sent him off by another route.

Here I must remark that the Giver of all good was merciful to me in preserving me, an unarmed lad, and consequently without the power self defense, for the same marauding band of assassinators killed several unoffending and innocent persons in cold blood on that same day. Among the number was a young man who had been married but the day previous. I was in their power for I was within a shorter distance than pistol shot.

Shortly after I gained the woods, I beheld people with wagons containing their families and moveables fleeing from the town and from danger. I staid out all day and knew nothing of the fate of Miss Elizabeth until I returned in the evening. She upbraided me in a very harsh manner for leaving her and threatened that as soon as Colonel Humpton should arrive, she would get him to flog me severely.

The Colonel, however, commended me highly when he did arrive. He stated to her that I had acted with more sense and caution in the matter for her safety than she could or would have done herself. “For had Sammy ran to the house, they might have followed him, captured you and recovered my old British regimentals and papers which might have betrayed me into their power.”

She was of a forgiving disposition of heart and before he arrived she had no doubt revoked her hasty decision. She spoke to the Colonel of my conduct upon that occasion but did not ask him in my presence to chastise me for it.

The Colonel’s harshness at all times was of rather a momentary cast. It would not have been a matter of great surprise to myself if he had flogged me at her instance for upon the day of his arrival an accident occurred which was well calculated in itself to have fretted him. He had a very valuable slut [female dog] that he had brought from England with him and which his niece had with her on the farm where we resided.

A dog in the neighborhood which was in the habit of killing sheep was often seen lurking about the premises. I had determined to shoot him if possible and had procured a large leaden bullet which I had made into slugs for the purpose. With my piece loaded with these I laid in waiting for him.

He at length came near and the slut springing forward just as I was in the act of pulling the trigger of the gun received one of the slugs into her head just above one of her eyes which caused her to reel about for sometime. I thought at first that I had really killed her but she was but little injured by it. I recollect that the Colonel besides cutting the slug out of her head, pulled my ear well for me as my punishment for the injury I had done. This, however, was a much lighter punishment than that which I should have endured within my own breast had I been so unfortunate as to have killed her.

The Colonel always seemed to relent his conduct of severity towards me, and as certain as he dealt in any way harsh with me he would shortly afterwards sing out, “Boy!” When I would go to his room he would hand me a bowl containing some “good stuff”—liquor (of which he always kept the best) saying, “My lad, here is something to drink.” This was a habit so peculiar with him and so uniform that his cook would often say to me when the Colonel pulled or boxed my ears, “Sammy, I wish the old fellow would come home and you would do some mischief, for then we would get a good grog.” Folks were not much worse in heart then than they are now. But they were better fellows of their grog then than they are now. I could divide with the cook and the cook could as generously divide with me.

From Somerset Court House Colonel Humpton removed us to one Garret Van Zandt’s (not far from Coryell’s Ferry) whose farm was worked by one Eber Addis. Coryell’s Ferry is situated in Jersey not very far from Trenton.

The Colonel had a grey horse which had belonged to the adjutant of the regiment (his name was Huston) who had been shot from off him at the Battle of Germantown. Huston having been killed when in the rear of the line, it was supposed that he was shot by some of his own men. He was said to be a rascally and tyrannical officer and from the fact also of his having been often threatened by his own men (among themselves) that he would be the first to fall in battle. Huston after he was shot (although shot dead) hung sometime on the back or rump of his horse before he fell off. As some confusion took place in consequence of the great fog on the morning of the Battle of Germantown, it is possible that he may have fallen through mistake as others of the American soldiers did by the hands of their own companions in arms.

Whilst we were at Van Zandt’s, a boy belonging to Van Zandt (and about my own age) and myself undertook to run our horses at times and to jump them over a pair of bars in order (besides the amusement it afforded us) to see which could make the most lofty leaps, he upon a horse that belonged to Van Zandt and I upon the Colonel’s grey charger. With good judges and a purse up, I would have been sure of drawing it with the Colonel’s horse.

For this mischievous frolic of the boy and myself, I recollect that the Colonel not only reprimanded me harshly but in addition pulled my ear severely. The Colonel set great store by this horse and such maneuvers as ours might have rendered him useless, jumping him over such high obstacles, which was well calculated to break a leg or otherwise injure him. And besides this, we stood a good chance to have broken our own necks at the time.

Chapter 8

[Pg. 152] >From Van Zandt’s I was detached for a time to Washington’s camp not far from Stoney Point. At this time (about the 1st of July 1779) an expedition was fitted out against Stoney Point, a strongly fortified post on the Hudson River. This expedition was entrusted to the brave General Anthony Wayne.

I was one of the musicians attached to the detachment. I do not recollect the number of men composing our detachment, but suppose it might have contained from 500 to 700 men. The number might have been much greater, and besides other covering detachments might have been out also.

When about to set out upon the march sometime in the afternoon, drums were beating, colors flying and soldiers huzzaing—each soldier full of spirit and entering largely into the spirit of the enterprise and full of expectation as to the wished results. The order was at length given to march and as we progressed therein we were ordered not to suffer our drums to make any noise and on each man was enjoined the most perfect silence.

A halt was called a little after sunset and I can recollect very distinctly that we were then so near to Stoney Point as to be able by climbing up into the tops of trees to behold the British soldiers walking backward and forward at the fort. I for one amused myself very much in eyeing them at a distance. General Wayne ordered the detachment on in silence, leaving the musicians (or at least a portion of them) myself included in the number behind him.

In going into battle it was customary for the Drum and Fife Majors to send a Field Drummer and Field Fifer along and among their duties this one, the beating a signal tune for an “advance,” another as a “retreat” and a third as a “parley,” etc.

As night closed in upon us our British brethren became totally lost to our view; more lost to view than we who were left behind could have wished. And whilst we were in the tops of trees and could behold them, we were wishing that we could have been permitted to have accompanied the detachment through all its movement. What our state of feelings would have been had we been along and the detachment made to smell powder in its war strength, I know not. However, I imagine that we would have strove to have joined in singing out (as they did upon a subsequent occasion) the long to be remembered watchword of “Remember the Paoli [Massacre].”

In the course of two or three hours the detachment returned to us again. The expedition proved a failure for in the midst of all the caution upon the part of our commander and the soldiers under his command, the British discovered them sooner than it was expected they would have done. Whether this was through the instrumentality of scouters or of their piquet guards, I do not remember.

General Wayne knew well that this was a remarkable strong position and knew well also the bold and hazardous nature of the enterprise. But he had the hope that he could have pushed his men on in quick time in order to gain the walls ere they should have been subjected to any great fire from the enemy. Our General being thus far frustrated in his design saw proper to abandon the design of attack for the then time being. He ordered a retreat to the American camp, but if he did, he successfully carried his purpose about two weeks afterwards in a second expedition on the night of the 15th of July. I was not permitted to join in this latter expedition, having been sent back (ere that day arrived) to Van Zandt’s again. Its execution was again given to General Wayne and the light infantry with a brigade as its cover and Major Lee and his dragoons as reconnoitering supporters. This was a daring assault and complete success crowned the bold effect.

The American soldiers preceded by a forlorn hope of 40 men in two divisions, having rushed forward up the precipice and gained the walls or outer barricades which consisted of several breastworks and strong batteries which were constructed. In advance of these and below them, two rows of abattis had been constructed also. The attack was made about midnight and the works taken by storm although the assaulters were subjected to a tremendous discharge of grape shot and musketry. General Wayne made a desperate attack with unloaded muskets and had therefore to depend for success entirely upon the bayonet’s point.

After a short but very obstinate defense the fortress was carried by storm and the garrison surrendered. Wayne killed 63 in the attack, among which were two officers, captured 543 British soldiers and became possessed of a considerable quantity of ordnance, ammunition and military stores.

This was a most gallant exploit—few if any were more so during the Revolutionary struggle. It was looked upon as among the most brilliant achievements of the American arms. Wayne (it was said) when passing through a deep morass previous to his gaining the bottom of the ledges of rocks upon which a portion of the detachment passed, sunk deep into the mire and in pulling his foot up, pulled it out of his boot. He then stooped down and plucked his boot out of the mud and carried it in his hand and pushed his men forward in his stocking foot, not even taking time to draw it on.

I do not recollect any thing that transpired worthy of notice after I returned to Van Zandt’s until I was again transferred from there by the orders of Colonel Humpton sometime during the fall of 1779 to some military post not far distant from West Point. There I remained for the most part (except when detached for a time to Crown Point) until after the execution of Major Andre, Adjutant General of the British army, who was hanged a spy in the fall of 1780.

Chapter 9

[Pg. 159] When we arrived at West Point it seemed to me that there was nothing in the country but encampments and none other inhabitants but soldiers. It was a strong and important military post. Here the Commander had concentrated a very great force. Soldiers were often arriving and often departing. There were a number of forts in the vicinity of West Point—Forts Lee, Putnam, Arnold and Defiance.

These forts were situated on high bluffs near to and commanding the North River. Our encampment was on the high or level land nearly a mile from the river. There were two or three brigades of soldiers laid here. New Windsor (now perhaps called Newbury) was about 5 miles up the river and was a great apple market and to which many of us soldiers often repaired to purchase apples.

The parade ground attached to our encampment at this post was the prettiest I ever saw anywhere during the Revolution. The soldiers were quartered in log huts. These huts were built in two rows with 15 or 20 feet space between the rows and extended for more than a mile. Very many of these huts were built at the time I was there with my father in 1777. The duty of the “Camp-colour men” was to level the parade ground and keep it swept clean every day.

West Point was a strong military post. It is true it might have been captured by a very strong force even at this time, with all the military force concentrated there, but in consequence of there being so many forts along the river and other almost impregnable barriers, it could justly have been termed a strong position. Below or opposite to the lower forts a great iron chain was stretched across the river from shore to shore and rested upon buoys or upon timbers to bear it up to within a proper distance of the surface of the water. The object of placing this chain across the river was to bar the enemy’s shipping from ascending the river. I am fully of the opinion that each link composing this chain was from 3 to 4 feet in length and from 3 to 4 inches in thickness, and weighed _____ lbs.

This chain was sunk so as to be cleverly under water. It was quite amusing to behold large sturgeon pitching up above it and then be caught upon it and lie dashing and fluttering about for a considerable length of times before they would succeed in extricating themselves from their iron elevated position of uneasiness.

To all these impediments were added floating and stationary batteries upon which heavy ordnance were planted and which in an emergency would undoubtedly have been well manned. I should think that nature and art combined would have been heavily taxed and would have had hard work to have pushed a vessel up the river above where this great chain lay moored.

Colonel Humpton frequently took me with him whist at West Point and other military posts to ride “the patrols” at night. It being generally very late in the night when we would go these rounds, I very frequently got very sleepy and would linger behind him. When I would do this, he would stop his horse until I would ride up to him. He would then quietly reprimand me, telling me at the same time that I did not know the danger I was in and for me to keep close and quietly behind him.

This going the grand rounds the Colonel was quite fond of, although a dangerous duty, especially where there were ignorant and cowardly men set as piquet guards. As he would advance towards a piquet guard the piquet would hail him by calling out, “Who comes there?” Colonel Humpton would answer, “A friend.” The piquet would then cry out, “Advance friend and give the countersign.” The Colonel would then advance and make as though he would advance upon him and pretend to coax or pass him. The piquet would then call out, “Stand friend and give the countersign.” The Colonel would be at the end of his sport with each piquet guard at this point of time, he had to give the countersign, or the next moment receive the contents of the piquet’s musket.

This was a perilous duty. Oftentimes a promise of reward would be made to a piquet guard for permission to pass. Instances however were very rare, that of soldiers suffering officers or others to advance and bribe them from duty. There have been instances however of piquets having suffered themselves to be tampered with. Sometimes soldiers not knowing their duty thoroughly when asked by an officer (knowing him to be such) and thinking that they were bound to obey his orders, finally consented to give up their muskets when asked by officers to let them look at their pieces to see if they were in good condition, etc. Should the piquet do this, the officer would immediately call out to another piquet guard and have the delinquent taken under guard and would afterwards have him punished for his dereliction in duty.

A camp or piquet guard (piquet especially) receives the countersign and his duty is to know no man, nor suffer himself to be tampered with by privates, officers or others, no not even by the General of Division. His duty is made known to him and the nearer he adheres to the line of his duty, the more does he evince his possessing the lofty ingredients and character of a true soldier and the more will he endear himself to his brother soldiers and superior officers.

As I made a somewhat lengthy stay at West Point after visiting it this time, I will endeavor to describe to my readers some of our soldier doings. Each morning we (the fifers and drummers) had to play and beat the Reveille at the peep of day and then the Troop for roll call. After roll call, a number of men would be called out of each company as camp and piquet guards and so many for fatigue duty—these were called Fatigue Men.

A drummer was also chosen and was called Orderly Drummer of the Day. This drummer had his drum constantly lying on the parade ground during the day. Its place was generally where the colours were planted or in other words, where the American standard was erected on a pole similar to what is now known and called a Liberty Pole. When the Sergeant of the fatigue men called out, “Orderly Drummer,” this drummer repaired to the Sergeant immediately, who ordered him as follows: “Orderly Drummer beat up the Fatigue’s March.”

We had a name for everything, or rather tunes significant of duties of all kinds. To beat the “Point of War,” and “Out and Out,” or through from beginning to its end, which embraces all tunes significant of Camp Duties, Advances, Retreats, Parleys, Salutes, Reveilles, Tattoos, etc., etc., would consume nearly or altogether half a day, and to beat the Reveille properly, “The Three Camps,” which constituted the third or last part, would consume from the peep of day until after sunrise. There are many good Drummers and Fifers nowadays that would not know what the “Point of War” is or should mean. Nor do they know what should be played or beat for a Reveille properly. Some at Baltimore in 1813 and 1814 beat “Sally Won’t You Follow Me?” and other tunes quite as inappropriate.

At West Point (as at all other military posts) the musicians knew at once when a particular roll or march was named, what tune to play, and the soldiers all knew at all times what duty was to be performed upon the hearing of the musicians “beat up.” When the Orderly Drummer would beat up the Fatigue’s March, all soldiers chosen for the day would repair to their post, form into lines and were marched off immediately and set to work. There was always a great difference manifested in the manner of attending the calls, “Fatigue’s March,” and “Roast Beef.” The soldiers at the Fatigue’s call generally turned out slowly and down hearted to muster upon fatigue parade. When an officer would sing out, “Orderly Drummer, beat up the ‘Roast Beef,’” and the musician fairly commence it, the soldiers would be seen skipping, jumping and running from their tents and repair to where the rations were to be issued out. That there would be a difference manifested will not be wondered at when it is stated that the Fatigue Men had to muster for the purpose of going to labor, chop, dig, carry timber, build, etc., etc., whilst the others would turn out voluntarily to learn what they were to draw for breakfast, dinner, etc.

To each regiment there was a Quarter Master attached who drew the rations for the regiment and to each regiment belonged a Quarter Master’s Sergeant that drew the rations for and dealt them out to the companies or delivered them in charge of the Orderly Sergeants of companies.

The Quarter Master’s Sergeant at a proper hour would take [several] Sergeants and as many men as might be necessary and repaired to the store house and slaughterhouse which were built at the edge of the North River and extending some distance into the river. These buildings were very large. These men always took poles with them that were kept for the purpose of carrying meat upon to the camp. They took also camp kettles with them for to carry vinegar, whiskey, etc. in to the camp. These men on their return were marched in front of their respective companies. The “Roast Beef” would then be beat up and the men understanding the music (which is a signal for drawing provision) would hasten as before mentioned and stand ready to receive their quota.

The Orderly Sergeant of each company divided the meat into as many messes as were in each company (six men constituting a mess) and then a soldier was made to turn his back to the piles. The Sergeant would then put his hand upon or point to each pile separately and ask, “Who shall have this?” The soldier with his back to the mess piles then named the number of the mess or the soldier that was always considered as head of the mess, and in this way they proceeded until all was dealt out.

Every man in each mess drew (when it was to be had) a gill of whiskey each day and often salt and vinegar when these were to be had. Sometimes when flour was [not] scarce it would be drawn every day. Sometimes we would draw three day’s rations on one day and sometimes none at all for two days together. Sometimes we drew baker’s bread and always when it was to be had. Sometimes we drew sea biscuit.

I have been down at our slaughterhouse at times for the purpose of assisting in carrying the provisions to camp and I have seen a great many cattle drove into it at a time. I recollect that once we had to wait until the butchers would kill. They drove upwards of a hundred sheep into the slaughter house and as soon as the doors were closed, some of the butchers went to work and knocked the sheep down in every direction with axes, whilst others [butchers] followed and stuck or bled them. Others followed these, skinned them, hung them up and dressed them. A very short time elapsed from the time they commenced butchering them until our meat was ready for us.

I recollect having been there at another time when they were killing bullocks. They drove a very large and unruly bullock into the slaughterhouse. This fellow they could not knock down. They had given him a great number of very hard blows upon his forehead but could not fell him to the ground. He at length broke away from them and left the building by jumping through a window. The butchers pursued him, caught him and brought him back secured by means of a strong rope. One of the soldiers belonging to our party happened to say (unguardedly) that had he had the knocking of him down, he would have had him down in a much shorter time than they had consumed.

The butchers dropped the bullock and all, and took after him [the soldier], butcher knives in hand. When they made the dash at him, first he ran, and when followed by them he had the hardest kind of work to save himself by running. Had they caught him, they in their anger would undoubtedly have plunged their knives as deep into him as they were prepared to do into the bullock.

I have known great numbers of very fine and fat cattle slaughtered there but if I have, I have seen many more poor and indifferent ones killed there also. But with these we had to be content in the absence of better.

Often the Orderly Drummer would be ordered to beat up the “Adjutant’s Call.” The Adjutant, when called thus, would answer to the call by his presence and would then receive his orders from a superior officer. Sometimes the orderlies would be ordered to beat up the “Drummer’s (or Musician’s) Call” at the hearing of which we (fifers and drummers) would have to drop all and answer by our presence. Our duties upon such calls were various. Sometimes we would be required to beat the Long Roll, Roast Beef, the Troop or the General, and sometimes “The Rogue’s March,” and sometimes “The W____’s March.”

I recollect that one day the Orderly of the Day beat up the Drummer’s Call and we immediately mustered at our post. In a few minutes after we had reported ourselves by our presence, a Corporal came along with a file of men and we fell in by placing ourselves at the head or in front of them. He then marched us to the parade ground. After remaining there a few minutes, a woman of ill fame was brought in front of us. In a few minutes afterwards we received orders to march. As we started off we commenced playing and beating up the “W____’s March” after her until we arrived at the bank of the river.

A halt being called, she was then conducted by the Corporal into the river until they both stood in water nearly or altogether three feet in depth. Quite a scuffle ensued when the Corporal attempted to duck her by plunging her head under water. The Corporal after a number of trials at last succeeded in executing this part of the sentence passed upon her. He plunged her, head and all, three times under the water and then let her go. When she started off after coming out of the water, we gave her three cheers and three long rolls on the drum and then marched back without our fair Delilah, follower of Bapta goddess of Shame.

Such frolics as these were often made a part of our duties and which (being young as some of us were) were enjoyed very well. It was not only viewed as a necessary conduct of severity to this class of unfortunate women, but it became necessary at least that they should be removed from camp. That course of treatment, it must be admitted, was harsh even to these unfortunate females.

Early in the evening we had to beat up “The Retreat.” We played and beat the Retreat down and up the parade ground as far as our regiment extended for “roll call.” We had many tunes that we played and beat for Retreat. “Little Cupid” was often played and beat for a Retreat. At bedtime we had to beat the “Tattoo.” For Tattoo we had many tunes also. For roll call in the morning we had many tunes that we played and beat as “The Troop.”